I. Introduction

When the Russian Federation unleashed its deadly invasion of Ukraine, it was fully aware unprecedentedly severe sanctions would be imposed1 . As a direct result of these completely foreseeably sanctions, and other knock-on effects of the invasion, Turkish and other foreign investors in Russia will have seen the value of their investments take a serious hit, with further hits certainly to come2 .

In the following, ASC Law addresses the possibility Turkish investors in the Russian Federation may have claims they can bring in arbitration under the solid, both substantively and procedurally, Turkey-Russia Bilateral Investment Treaty (the "Turkey-Russia BIT")3 . At the same time, we consider the similarly strong Turkey-Libya BIT, given Libya is also a country in which Turkish investors saw the value of their investments devastated by war, i.e., after the early 2011 anti-Gaddafi hostilities quickly morphed into a full-scale, many-year insurgency4 .

Finally, we will discuss two arbitral awards, Öztaş Construction v. Libya et al. (ICC Case No. 21603) Final Award, 14 June 2018 and Cengiz Construction v. Libya (ICC Case No. 21537) Final Award, 7 November 2018. We will consider these awards, issued by tribunals constituted pursuant to the Turkey-Libya BIT, and what light they may shed on the strength of any claims arising under the Turkey-Russia BIT.

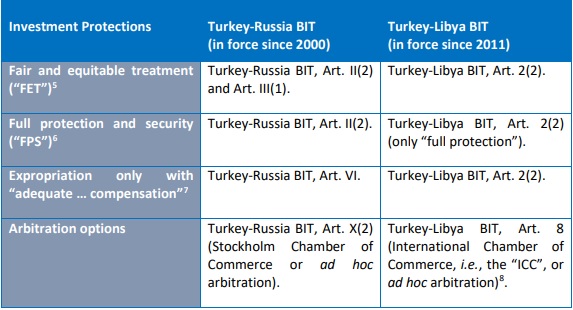

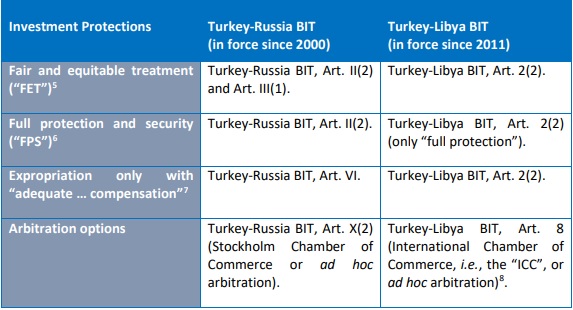

II. Investment Protections Found in the Turkey-Russia and Turkey-Libya BITs

The following chart sets forth several of the primary investment protections found in the Turkey-Russia and Turkey-Libya BITs, which are quite robust.

The most important of these investment protections is the promise of "fair and equitable treatment", i.e., FET, which "is intended to give adequate protection to [an] investor's legitimate expectations". Impregilo S.p.A. v. Argentina (ICSID Case No. ARB/07/17) Award, 21 June 2011, ¶2859 . FET protection, while quite meaningful, is more limited than might be expected, with generally speaking more than simple negligence by the host State required. As one arbitral tribunal has explained, FET's "ordinary meaning" requires "'just,' 'even-handed', 'unbiased'" and "'legitimate'" treatment of foreign investments, with the "infringement" of FET requiring "'treatment in such an unjust or arbitrary manner that the treatment rises to the level that is unacceptable'". Tulip Real Estate v. Turkey (ICSID Case No. ARB/11/28) Award, 10 March 2014, ¶401.

III. Is Russia in Breach of the Turkey-Russia BIT?

A. Likely a matter of "first impression"

Whether an invasion of another country by a State hosting foreign investors would be found to be a violation of treaty-based investment protections, given the arguably "indirect" nature of the damages those investors would suffer, is likely a matter of first impression10. Nevertheless, it would appear, to the authors of this piece, that such claims, at least prima facie, would have merit. We address two arbitral awards below, in Öztaş Construction v. Libya and Cengiz Construction v. Libya, which involved allegations of damage suffered by war in the host State itself, and what they suggest for the purposes of this piece.

B. Viability of any treaty claims depends on the specific facts and applicable law

Whether any given Turkish party doing business in Russia would have viable claims under the BIT would depend on the specific facts and applicable law pertaining to its particular Russia-based activities and, indeed, whether those activities would even be considered an "investment" covered by the BIT. Just as important would be the nature, and magnitude, of any damages suffered.

For example, Turkish businessessimply selling productsto Russian counterparties would likely not to be found to have made an "investment" in Russia. The consensus in investment arbitration case law is that mere cross-border sale of goods is not an "investment" protected by investment treaties. See, e.g., Global Trading and Globex v. Ukraine (ICSID Case No. ARB/09/11) Award, 1 December 2010, ¶56.

With regard to the nature, and magnitude, of any damages suffered, because treaty-based arbitration is both expensive and time consuming, resort to it is limited, as a practical matter, to investors who have suffered substantial damages11. Certainly Turkish contractors are finding their work in Russia significantly more difficult post-invasion, as it may now be close to impossible to obtain the materials and workers they need and, even if obtained, paying for them (given the Ruble's collapse, limits put on the use of other currencies, a steep rise in inflation, difficulties in accessing bank accounts, etc.). Whether such damages justify initiating investment arbitration, however, is another question all together.

C. Are Öztaş Construction v. Libya and Cengiz Construction v. Libya "cautionary tales"?

The answer to the question posed in the above caption, for the authors of this piece, would be no. Indeed, the tale they tell should cause Russia great concern. Although any damage suffered by Turkish investors in Russia as a result the invasion of Ukraine is arguably less direct than that suffered by the claimants in Öztaş Construction v. Libya and Cengiz Construction v. Libya, it was the Russian Federation which "triggered" the Ukraine invasion, leaving Turkish investments exposed to enormous economic consequences. The actions of Libya, or lack of action as the case may be, pale in comparison.

1. Öztaş Construction v. Libya

Öztaş Construction and the state-owned LIDCo entered into a contract, in 2008, whereby the Turkish contractor was to build and operate a water supply and transport system. Presumably as a result of the civil war unleashed by the anti-Gaddafi hostilities, the parties executed a termination agreement in 2013, pursuant to which LIDCo was to pay the claimant approximately LYD3.5 million (US$2.8 million). LIDCo, however, failed to make those payments. Öztaş Construction v. Libya, supra, ¶¶62-63 and 65.

Öztaş Construction initiated an ICC arbitration in 2016 pursuant to the Turkey-Libya BIT. In the 2018 Award, the tribunal majority, when considering whether Libya had failed "to provide commercial and legal protection and a stable and predictable legal and business framework", first observed, "[a]s a matter of international law, the condition of civil war or uprising ... constitutes an extraordinary situation that negates any negligence or lack of due diligence against the State of Libya". Id. at ¶16212

More importantly, for the present purposes, the tribunal majority then stated:

Claimant has not shown ... Libya has taken measures that directly aggravated or triggered the civil war and resulted in Claimant's alleged losses". Ibid. (emphasis added)13.

That cannot be said about the Ukraine Invasion, or about any resulting damages. Russia itself, by its own aggressive acts, without doubt "aggravated, and, indeed, "triggered", this "extraordinary situation".

2. Cengiz Construction v. Libya

The Turkish Cengiz Construction entered into two contracts in the late 2000s with the Libyan Housing and Infrastructure Board. Pursuant to these contracts, the claimant was to "master plan, design and build" certain "integrated infrastructure" in Libya's south. Cengiz İnşaat, supra, ¶¶2 and 94-95.

After "anti-government protests" had escalated into "violence and civil war", Cengiz Construction's projects were abandoned. In 2016, it initiated ICC arbitration pursuant to the Turkey-Libya BIT, alleging its "investment was completely destroyed and rendered worthless". Id. at ¶¶3 and 100-101.

The tribunal, in its 2018 Award, unanimously found Libya had breached its promise of FPS, in particular its "negative obligation to refrain from directly harming the investment by acts of violence attributable to the State". Id. at ¶¶403 and 43514. As a result, Cengiz Construction was awarded damages of US$52.2 million and arbitration costs of US$469,700 and €33,205, with interest to accrue on those amounts at LIBOR-plus 2%. Id. at ¶693.

IV. Final Thoughts

As explained above, whether any given Turkish investor may have viable claims under the Turkey-Russia BIT will depend on the specific relevant facts and applicable law. Nevertheless, it is important that foreign investors know the nature and quality of any protectionsthey may have under investment treaties, something ASC Law recommends be considered as part of its clients' pre-foreign investment due diligence. Moreover, and in any event, knowing one's rights, even if not exercised, is always valuable, as such knowledge may provide crucial leverage in the event disputes arise with one's counterparties.

In closing, it has been said Russia's brash invasion of Ukraine has "overturned the post-war world order", while the "old order — with its Cold War attitudes, militaries, alliances and enmities — is reclaiming center stage"15. But one important feature of the post-cold-war world order remains, which is the result of the proliferation of investment treaties over the course of the past 30 or so years.

These treaties, and their concurrent creation of what we would call a "private right of action", have left signatory States with a little less room to manoeuvre, given foreign investors may now directly pursue, in arbitration, claims for harm suffered due to the wrongful acts of these States. Such harm, in the not-too-distant past, would only have been capable of redress through diplomatic efforts and/or the often-unpalatable option of pursuing claims in the local courts of the very States that have harmed the investments in the first place. This new feature of the post-war world order would seem here to stay.

Footnotes

1 Russia is certainly no stranger to such sanctions, having been severely sanctioned as a result of its annexation of the Crimea and the "asymmetric" war it has been fighting in the Ukraine's Donbass region since 2014. Russia itself has been quick to sanction claimed acts of aggression, witness the sanctions it imposed against Turkey and Turkish businesses operating the Russian Federation, after it claimed Turkey, in late 2015, downed a Russian warplane over Syria. One of authors of this piece, Mr. Mark D. Skilling, considered possible claims under this same BIT in a 2016 piece written about these sanctions imposed by Russia, some of which were directed at Turkish businesses operating in Russia. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/russia-turkey-talk-sanctions-mark-d-skilling/.

2 According to Turkey's Ministry of Foreign Affairs, "[t]rade volume between [Turkey and Russia] has reached 30 billion USD in 2021. More than 2000 projects with a total value of over 80 billion dollars have been realized so far by the Turkish contractors in Russia ...". https://www.mfa.gov.tr/relations-between-turkey-and-the-russian-federation.en.mfa.

3 The Turkey-Russia BIT was signed in 1997 and came into force in 2011. The English version of this BIT can be found at: https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/international-investment-agreements/treaty-files/2231/download.

4 The Turkey-Libya BIT was signed in 2009 and came into force in 2011. The English version of this BIT can be found at: https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/international-investment-agreements/treaty-files/5021/download.

5 Impregilo S.p.A. v. Argentina (ICSID Case No. ARB/07/17) Award, 21 June 2011, ¶285.

6 FPS "does not impose .... a 'strict liability' obligation. ... That is, the State cannot insure or guarantee the full protection and security of an investment". Tulip v Turkey, supra at ¶430. See also Azurix v. Argentina, (ICSID Case No. ARB/01/12) Award, 14 July 2006, ¶408 (FPS also includes providing "a secure investment environment").

7 A commonly accepted definition of "expropriation" is when, due to the actions of the host state, the subject assets have "'lost their value'" or "'economic use'" for the investor. See, e.g., Compania and Vivendi Universal v. Argentina (ICSID Case No. ARB/97/3) Award, 20 August 2007, ¶7.5.12.

8 ICSID arbitration is also provided for, but this option not available until, and if, Libya joins the ICSID Convention. 9 The other protections can be said to be, to a large part, derivative. See, e.g., Azurix v. Argentina, supra, ¶408 ("persuaded of the interrelationship" of FET and FPS) and Impregilo v. Argentina, supra, ¶334 (where "there has been a failure to give" FET, it is "not necessary to examine whether there has also been a failure" to give FPS).

9 Tulip Real Estate v. Turkey (ICSID Case No. ARB/11/28) Award, 10 March 2014, ¶404.

10 About any damages here being indirectly caused by the invasion, the Permanent Court of International Justice, in its oft-cited and followed Factory at Chorzów decision, stated "reparation must, as far as possible, wipe out all the consequences of the illegal act and reestablish the situation which would, in all probability, have existed if that act had not been committed". Factory at Chorzów, PCIJ Series A No. 17, ICGJ 255 (1928), p. 47. Damages falling under this measure would, it seems, accurately be described as those directly caused by a State's wrongful actions.

11 According to a recent survey, the mean legal costs incurred by states in investment arbitration proceeding are around US$4.7 million, with the median figure some US$2.6 million. For investors, the mean costs exceed US$6.4 million, and the median figure is US$3.8 million. At the same time, the average length of these proceedings is between four years three months and four years eight months. 2021 Empirical Study: Costs, Damages and Duration in Investor-State Arbitration, jointly conducted by the global Allen & Overy law firm and the British Institute of International and Comparative Law. 136_isds-costs-damages-duration_june_2021.pdf (biicl.org).

12 The majority had already concluded it had no jurisdiction over the state-owned LIDCo, and found Libya could not be found liable based on LIDCo's actions as it had not breached the BIT and it thus "follows logically there can have been no breach" by Libya "whether or not" LIDCo's acts could be attributed to Libya. Id. at ¶140.

13 The dissenting arbitrator believed Libya should have been found in breach of both FET and FPS, concluding among other things it had neither "maintained" a stable framework for investments nor showed sufficient efforts to rebuild it, despite the fact that more than six years has passed following" the break-out of the Libyan Civil War". Öztaş İnşaat v. Libya et al. (ICC Case No. 21603) Dissenting Opinion,

14 June 2018, ¶¶28 and36. 14 The tribunal also found Libya had breached its "positive obligation to prevent that third parties cause physical damage" to foreign investor's investments, an obligation also part of its promise of FPS. Id. at ¶¶403 and 448.

15 "We must end the war on Ukraine and put an end to perpetual wars", Heuvel, Washington Post, 1 March 2022.

Originally Published 18 March 2022

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

Mark D. Skilling

Aksu Caliskan Beygo Attorney Partnership (“ASC Law”)

Esentepe Mh

Harman 1 Sk. No 5 Harmanci Giz Plaza Kat 3-8-15-16

Sisli

Istanbul

34394

TURKEY

Fax: 212284 9883

E-mail: info@aschukuk.com

URL: www.aschukuk.com

© Mondaq Ltd, 2023 - Tel. +44 (0)20 8544 8300 - http://www.mondaq.com, source Business Briefing